Let’s Not Gaslight Kids: Age and Power in SDE by Haley Tilt and the PFS Family

This October, PFS held elections for clerkships of the committees that keep the school running - media, fundraising, mediation, admissions, and many others. We saw record highs for the number of students who volunteered for leadership roles on these committees, with kids signing up to serve as clerks and deputy clerks.

This development has stirred up questions among the staff about how age-based power works at PFS. As staff began discussing this theme, students have joined our conversation, deepening and challenging some of our assumptions. The content and language in this post has been adjusted multiple times as staff and students have read, discussed, edited, re-read, and re-edited the post. In particular, vocabulary has been changed so that the post is accessible to a broader audience at varying reading levels. Where students felt that a word might be inaccessible to some readers but did important work, we have included a link to a definition.

Though I shift between ‘I’ and ‘we’ throughout the post, the ideas contained in my words were developed out of several conversations with staff and students and represent a collective journey towards a better understanding of power relations within our community.

I’m still new to democratic and self-directed education, but I’ve noticed a trend - when adults speak about these spaces, they often say that kids have ‘equal power’ with adult staff. Most recently, I saw this sentiment expressed in an old PFS blog post: “At PFS, every School Meeting member (students + staff) has equal power in running the school and governing their own learning. Students are learning in a true working democracy, where each individual has the same rights, regardless of age, race, gender, or academic achievement… At School Meeting, each of these students (and the staff they elect) gets one vote, a vote no more or less powerful than any other.”

I’ve heard several variations on this theme, sometimes from my own lips. It’s a pretty idea. And it’s also transparently wrong.

We realize this may be a controversial statement to some. Adults who have committed their energies to holding egalitarian spaces for children might reasonably take offense at this claim. But we must distinguish between our aspiration towards equal power and the reality of systemic inequality. In the world outside our little democracies, kids, BIPOC, women, disabled, poor and working class people do not have equal power with those who hold privileged identities. That world doesn’t disappear when School Meeting starts.

The first truth we need to confront is that an equal vote does not mean ‘equal power’. My ability to accomplish my goals - through influence, speech, relationship, intimidation, or other means - is ‘power’. My actual vote in School Meeting or JC is just one tool (and a fairly minor one) for accomplishing my goals.

No one’s put this better than Jabrea, a PFS alum. In a recent interview, Jabrea told me, “I could challenge staff, and I think they liked that about me, and I didn’t want to give them what they wanted. Sometimes I would participate in School Meeting, but when staff were asking me to be there, I didn’t want to feel used, so I didn’t give them the satisfaction of hearing me talk.” Jabrea’s statement is a sophisticated analysis of power dynamics in the school. Aware that her speech could be co-opted within the dynamics of School Meeting and adult privilege, Jabrea spoke, but only on her terms. She didn’t need School Meeting to express her power; to the contrary, School Meeting could hinder her power.

For those who wish to perpetuate inequality, confusing ‘equal vote’ with ‘equal power’ is a useful weapon; by emphasizing that less powerful people could exercise their vote, they deny the existence of structural and relational power that benefits them.

For the vast majority of free school educators who genuinely wish to support kids in finding their own power, equal vote = equal power is a counterproductive fallacy. Let’s not gaslight kids by pretending that they are just as powerful as adult staff.

When we accept this premise, we distinguish between the world as it is and the world as we wish it to be. As democratic educators, we want to help children find their power. We want to establish new ways of relating to kids on equal terms - not just in the formal structures of our school, but also in our interpersonal dynamics.

Knowing that our vision of establishing equal relationships with kids will always be aspirational, we set two goals that will move us in that direction. First, we seek to better understand how students navigate and exercise power in our school community. Having discarded the belief that equal vote = equal power, we must attune ourselves to the many forms of power in our school. Next, we analyze the role adults play in students’ exercise of power - where our intervention has been helpful, where unhelpful, and where irrelevant.

By analyzing the fabric of power at PFS and the role adults play in shaping it, we hope to do better - to draw closer to our goal of helping kids find their power alongside us.

The Fabric of Power at PFS

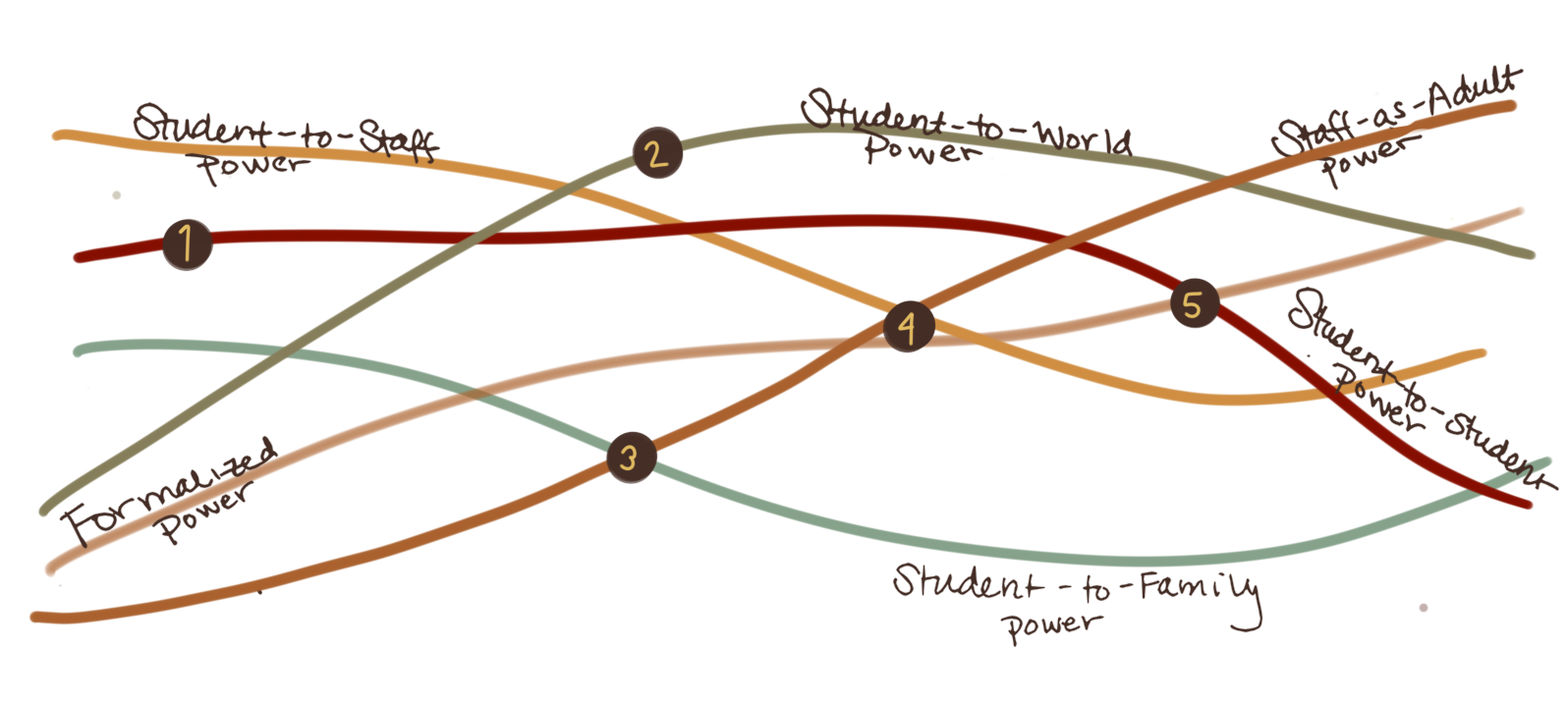

In this analysis, we discuss five ‘strands’ within the fabric of power at PFS. These are:

Formalized Power (School Meeting, Committees, Judicial Committee): Kids make use of formalized power in the school every time they participate in School Meeting (shaping the rules), write a student or staff up (invoking the rules to address a wrongdoing), or participate in a committee (using official structures to do collective work).

Student-to-Student Power: Peer-to-peer interactions are the most common way kids are practicing power at PFS. This type of power is often out of adult view.

Student-to-Staff Power: Students can choose to exercise their power on adults within the formal structures of the school, but they don’t have to. Often, a student’s insightful comment or telling action has a strong impact on staff thinking and decision-making.

Student-to-Family Power: For most kids, PFS is the second most important institution that they exist within - the first being their family. Kids are also working to navigate power within their families, usually from a disadvantaged position within the adult-child hierarchy.

Student-to-World Power: As kids get older, they become more embedded in the power structures of their workplaces, neighborhoods, and broader social and political worlds, but even younger kids are already working hard to find power in the world. This is true for all kids, but especially kids at PFS, where our open-campus policy blurs the boundaries between school and world.

Staff-as-Adult Power: Staff members possess greater power than students as a function of their position within our society’s pervasive adult-child hierarchy. Because of its systemic nature, adult power pervades all aspects of the school.

These ‘threads’ are not the only way we could analyze power at PFS, and as a postscript to this post, we’ve included a discussion on why we selected these categories. For now, it’s important to note that our categories don’t explicitly include racial power even though race influences all of these relationships. Jabrea’s quote speaks to that - her concern that her voice could be co-opted in School Meeting can be read from the perspective of age-based and race-based power. While we acknowledge that we can never fully isolate different types of power, this discussion focuses on age-based power. We leave a detailed analysis of racial power at PFS to another day.

Kids Practicing Power

To illustrate how kids navigate power at PFS and how adults participate in their efforts, we share five anecdotes about Solomon, Jackson, Brittany, Noah and Nadja, and Madison. We’ve picked these students and stories hoping that they will demonstrate the diversity of ways in which kids practice power at PFS.

1. We start with Solomon. A dominant voice in his friend group, Solomon offers a great example of a students exercising Student-to-Student Power, the most common type of power that students jockey for, try on, set limits for - in short, practice.

Sometimes Solomon’s exercise of student-to-student power intercepts the school’s formalized power. When he invented loopholes in our off-campus policies to expand where he and his friends can play, when he stopped School Meeting to collect other students on an important vote, or (more often) when he has beckoned his friends out of School Meeting back to their game, Solomon has navigated the formal power of the school.

But more often than not, Solomon’s power with other students isn’t on display to adults. He’s practicing with his friends, getting feedback from them, and refining the way he uses his power. We might snatch glimpses of this practice - when he gives a direction and others follow - but he’s not seeking our witness or participation.

Solomon hasn’t always been this effective at getting others to follow his lead. Staff remember a time when Solomon spent a great deal of time in JC. After repeatedly violating rules and his sentences, Solomon received a devastating sentence - in order to show that he respected the authority of School Meeting, he would have to go a week without wearing a costume to school (costumes being one of Solomon’s greatest passions).

Since then, Solomon has gotten much better at exercising peer-to-peer power effectively. The school’s firm boundaries, enforced primarily by other students, have given him a framework in which to practice. By contrast, Solomon has almost no tolerance for adult power; only recently has he begun meeting adult requests with anything other than a firm ‘no’. (Characteristically, my request that he read this section and give me feedback was also met with a firm ‘no’.) In his case, it seems that the best way staff can help him learn to navigate power is to let his peers check him - and otherwise get out of the way.

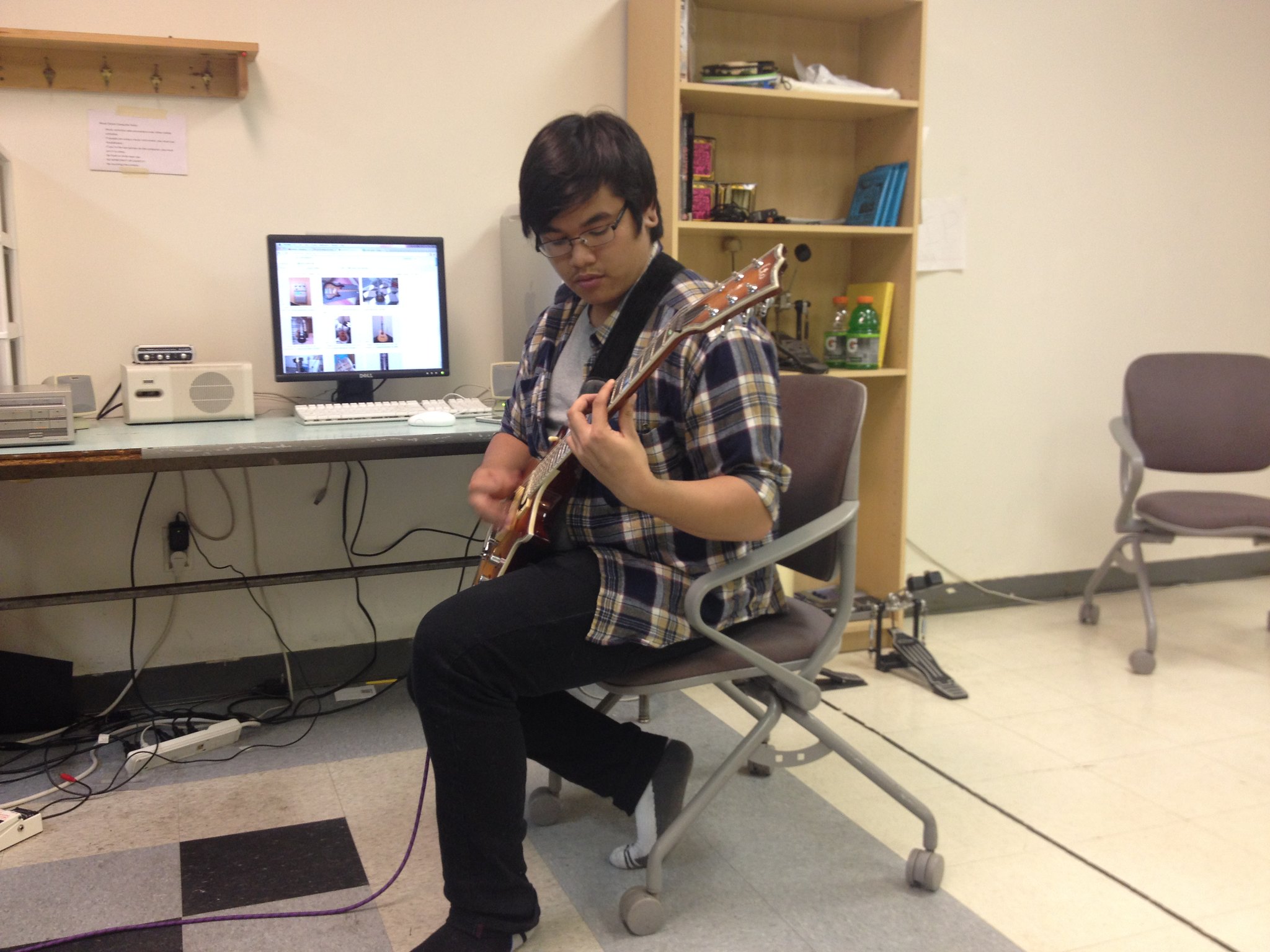

2. When he thinks about kids learning to navigate their power in the world, staff member Joel immediately goes to Jackson. As a member of Jackson’s graduation committee, Joel remembers other staff being skeptical that Jackson was prepared to graduate and wondering what Jackson had even done in his time at PFS. When he had been on campus, Jackson played guitar and slept. Often he hadn’t even been on campus. He’d expressed little interest in the formal power structures of the school, rarely attending School Meeting and serving as JC Clerk only once.

It was through Jackson’s graduation process that Joel learned about how Jackson had been finding and exercising power, not necessarily at the school, but in the world at large. At different points, Jackson had been working out the details of gigs and sponsorships for his band, caring for little cousins, and translating for his Vietnamese parents when they tried to buy a house.

Much like Solomon’s exercise of Student-to-Student Power, Jackson’s power had little to do with the formal structures of the school or the staff, so it was largely invisible to them. Some staff members doubted that Jackson had done anything worthwhile. Joel, a firm believer that it’s not his place to evaluate how a child spends their time, wasn’t (and still isn’t) so quick to judge. He’s also not one to intervene. Speaking with Joel, he’s acutely aware of his power as an adult and the drawbacks of exercising this power. Thinking back, Joel sees in Jackson’s story confirmation that his approach of non-judgemental non-interference works - at least for some kids, who just need the space to figure out their power and place in the world. It’s our job as adults to get out of the way.

3. Last year, Brittany’s* mom Tamara contacted a staff member to warn him that Brittany’s dad might try to meet Brittany at an upcoming school field trip. Tamara told the staff member that, although Brittany would not want to meet her dad on the field trip, she would be too scared to tell him to leave. Tamara was clearly anxious and asked if there was anything the school could do to intervene.

The staff discussed the issue. How could they intervene? Should they intervene at all? After all, Tamara had provided few details and both parents were listed on Brittany’s paperwork for the school. Then again, what if the staff’s failure to intervene endangered Brittany? One staff member suggested asking Brittany directly whether she would like the staff to intervene. Another worried that this would bring the conflict from home into the school, perhaps the one place where Brittany could set those worries aside. In the end, they decided it was better not to do all this deciding without the one person whose perspective mattered most. A staff member pulled Brittany aside. Brittany confirmed that she wanted support, but worked out her own plan for how she would evade her father if he showed up. All she needed was for staff to play the roles she devised for them in her plan.

We’ve located this anecdote at the intersection of Student-to-Family Power and Staff-as-Adult Power. Though the Sudbury model limits the influence of parents within the school, it is impossible (and I think, undesirable) to try to create a firm boundary between a child’s family life and their school life. In this (and sadly, probably many other) moments, Brittany was doing the scary work of navigating very uneven power dynamics within her family, and those were going to bleed into her life within the school, regardless of whether staff took action. I believe the staff recognized that it wasn’t their job to shelter her, but to offer their support. In deciding to center Brittany’s agency over that of her mom or dad, staff used their adult privilege as best they could - by doing what a child asked them to do.

As a child who was frequently weaponized in my parents’ divorce, this story impacted me deeply. My life would have been very different had all adults respected my autonomy and offered their allyship. It was beautiful to hear staff recall how they worked through this process and finally decided to center Brittany’s agency.

*Names and details in this story have been changed to conceal the identities of those involved.

4. As the former clean-up clerks, students Noah, Nadja, and staff member Mark were responsible for coordinating daily clean-up. When they inherited the clerkship, they decided together that the complicated clean up procedures were creating unnecessary conflict. They met to develop simpler procedures. Together, they decided that Noah and Nadja would check in with different clean-up zones and assign clean up jobs to new students. Mark would handle the paperwork, like posting lists of clean up tasks.

When Simon joined the staff, he replaced Mark on the clean-up committee. As a newcomer to the school, Simon approached Nadja and Noah with humility: “I needed to ask a lot of questions.” After Nadja and Noah had trained Simon, he continued working side-by-side with them, much as Mark had done. Over time, students have taken on increasing responsibility in this clerkship. In the most recent Clerkship elections, two new students introduced a motion to become clean-up clerks. For the first time at PFS, students are running clean-up without the support of a staff member.

We lift up Noah, Nadja, Mark, and Simon as an example of the way staff can work side-by-side with kids as they develop their power. Nurturing students’ power through this type of partnership often requires adult staff to strike a careful balance between managing students and staying out of their way. Developmentally, kids are still learning how to follow through on commitments and manage their time. Sometimes they need a bit of help. Mark remembers gently prompting Noah, “so, are we going to have that meeting?” I’ve seen Simon nudge Nadja to update outdated clean up assignments. But Mark and Simon are also careful not to become managers, knowing that their adult power can quickly snuff out kids’ burgeoning exercise of power and leadership.

Having attempted to co-lead in projects with students, I know how tricky it can be to strike this balance. I have often stumbled over the line, prioritizing the project’s completion over my young co-leader’s status as my equal, thereby undermining their investment in the project. As long-standing participants in Sudbury environments, Mark and Simon are more practiced than I am. They’ve also worked to cultivate comfortability with some degree of imperfection; they believe that kids’ leadership is more valuable than a pristine school.

5. Late in September, Madison exerted her power as School Meeting Chair. It was a particularly weighty moment in School Meeting, and even though plenty of students were in attendance, most were silent. Only a handful of voices - five staff and five students - were speaking. Several of the speakers had urged the silent participants to chip in, but most kids remained silent. Madison, who had been patient and allowed significant discussion, finally said, “how about a raise of hands?” and posed the two options. Everyone raised their hands, and the group quickly gained clarity on a challenging issue.

We see Madison exercising at least two types of power here. First is the formal power of School Meeting and her position as School Meeting Chair. It’s from this position that she was able to open a new way for students to participate (raising hands like this is not a typical form of participation in School Meeting). At the same time, Madison was using her power as a student with other students. It’s unlikely that a staff member or another student would have asked for a raise of hands, but if they had, students may not have responded. Within the school community, Madison is a gentle, patient, and sensitive presence. These qualities uniquely positioned her to exercise her power and encourage other students to exercise theirs in turn. By using her sensitivity to others’ emotions and her clout with other students, she was able to bridge the gap between what was being asked of the quiet kids (speech) and what they were comfortable with (silence), creating a middle ground that allowed them to participate.

Though Madison is to be credited with her actions, adults did play a role in empowering her prior to this moment. Quiana, one staff member, had gone to Madison early in September and nudged her to become School Meeting Chair, telling her briefly, “you should do it.” Quiana’s approach is notably different from Joel (who would never encourage a student to take on a leadership role if they had not initiated it themselves), but the students she’s encouraged have done well in their leadership roles and been glad for the experience. Much like Madison, we think that Quiana’s personality and positionality as a warm and nurturing black woman gives her a window to push many kids in a way that remains non-coercive.

So Power is Complicated… What Now?

We’ve picked these five anecdotes because they highlight some of the many ways kids at PFS learn to navigate and practice power. In discussing these anecdotes among staff and with students, we feel our vision sharpening.

As we sharpen our vision to how kids exercise power at PFS, we also begin to see how our interventions have impacted that exercise - for better or worse. Collective reflection has helped us understand how each of us navigates our power with kids and to see the strengths of each approach.

With his commitment to non-judgemental non-interference, Joel enriched our discussions by emphasizing how easily adult power can overshadow the power and initiative of kids and how quickly adult judgement can create value systems that elevate some children’s pursuits over others’. He reminds us that if we occupy space, kids are unlikely to challenge us for it. We must be proactive in creating space for kids to lead and we must be vigilant to check our power. Often, kids don’t need our help - they just need us to get out of the way.

Mark and Simon’s approach to partnership with kids underscores the value of shared work. Working shoulder to shoulder with young people requires adults to be thoughtful in how they relate to their young co-workers - too little support, and the project may fall through; too much support, and adults become managers, not colleagues. Striking this balance calls on adults to prioritize people over product and to continually reflect on how they show up with kids.

Considering the way Quiana has nudged students into leadership roles added depth to our understanding of how power can work. Compared to Joel’s approach, Quiana’s might appear heavy-handed or even (gasp!) coercive. But that’s not how it’s born out. Quite the opposite, Quiana’s nudging has led kids to exercise power in ways they might not have pursued on their own initiative. Her relationships with many kids allow her to push them in a way that other staff could not. These relationships are part of her power, and also part of the way she empowers kids.

Brittany’s story adds another layer to our analysis of power. It reminds us that children are always navigating the power structures of adult society that always render them subordinate, whether they’re at home or at school. Sometimes the best thing we adults can do is try to be good allies, deploying our adult privilege in the ways they ask us to.

At other times, we may not have the luxury of asking kids how or whether they’d like us to intervene on their behalf. All the of the anecdotes in this post describe interactions in which adults were being conscious of their uneven power and trying to make space for kids. But that hasn’t always been the case at PFS. There have been moments when adults intentionally wielded their power over kids.

In moments when adults have bullied children in our community, other staff haven’t always been sure whether or how to intercede. On the one hand, asking kids to advocate for themselves (in School Meeting, JC, or elsewhere) against another adult is unfair, in the same way it’s unfair to ask any marginalized person to do all the work of advocating for themselves on an uneven playing field. On the other hand, our democratic environment is one of the few environments where kids have any chance at advocating for themselves against the uneven power of adults.

Speaking with kids confirms the complexity of these dynamics. Faced with adults who tried to dominate them, some kids have been glad that other adults stayed out of the way and allowed them to advocate for themselves. For these kids, standing up against an adult on their own was empowering - it helped them to find courage that they’ve transferred outside the support of our democratic environment. For other kids, it felt profoundly unjust and frightening when adults did not intercede on their behalf. The fact that these other adults kept up the pretense that the kid could advocate for themselves on equal terms (the equal vote = equal power fallacy) was frankly insulting. We wonder then - how are staff to know, in the moment, whether a child wants our support? Quiana’s response is that we don’t know, we can only feel in the moment what is needed of us. I hear what she means, but I’m not quite so confident in my intuition.

As a staff, we aspire to establish equal relationships with children. We also acknowledge that this is difficult, if not impossible, because our world’s adult-child hierarchy doesn’t disappear when we step into our little democracy. Our discussions have revealed how challenging and tangled the fabric of power is in our community - challenging to navigate not only for kids, but for adults as well. Despite the difficulty, we believe that if we’re going to make progress towards equality, we adults must do the work to develop a fuller analysis of age-based power and the role we play in those power dynamics. The discussions that have informed this blog post are one step in that direction.

Postscript: A Note on These ‘Threads’

We’ve picked these five threads (Formalized Power, Student-to-Student Power, Student-to-Staff Power, Student-to-Family Power, Student-to-World Power, and Staff-as-Adult Power) not because they’re comprehensive of power dynamics at the school (they aren’t), but because they comprise semi-autonomous aspects of power. They also center relational dynamics (compared to an alternative, theoretical set of strands that center actions like ‘speech’, ‘movement’, ‘violence’, ‘facial expressions’). To us, centering relational dynamics in our categories makes sense because the exercise of power always involves relationships - between individuals, groups, or structures. This method of categorizing also highlights interactions between dominant and subordinate groups, thereby acknowledging the pervasiveness of the adult-child hierarchy into which we’ve all been socialized.

However, this method of categorization simplifies or omits several important aspects of power. For example, we haven’t explicitly included racial power, which deserves equal treatment. Racial power pervades each of these threads - from its impact on the way staff hear students’ voices to the way peers exert influence on each other. Acknowledging that racial dynamics at PFS deserve their own treatment, we leave that analysis to another day, simply stating here that race, like age, runs through all interactions in the school because they are both part of the ‘smog’ of systemic privilege and oppression in our society.

As a visual aid, we present an illustration of the threads that make up the fabric of power at PFS. We see this as a close-up view of the fabric; in its totality there are many more threads and intersections, with threads diverging at times, running concurrently at others. Along the threads we’ve plotted our six anecdotes of students navigating and exercising power within the context of this fabric.